I used to practice escrima on a rooftop of an old Baptist church in Manila during the early 1990s and in the process befriended a fatherly figure by the name of Manong Rudy.

Manong Rudy who was in charge of the security of that building is a burly Visayan ex-amateur boxer. One day, he gave me a hardwood fighting stick as gift and narrated an anecdote about his hometown, “Escrima is really good,” he says, “An escrimador in my hometown once fought and defeated a bolo-wielding assailant just by using the wooden peg where he tied his carabao to.” That was the first true-to-life story I’ve heard of how an escrimador fought and won a fight using an improvised weapon.

The pragmatic and deadly nature of the Filipino martial arts lies in the mindset that the fastest way to win a fight is by using weapons hence the utmost importance of the study of improvised weaponry. This is due to the possibility that when an encounter occurs, the escrimador’s weapon of choice might not be present.

The following excerpt from the book “The Filipino Martial Arts” by Dan Inosanto, Gilbert Johnson and George Foon explains escrima’s approach to variable weaponry, it reads, “Escrimadors claim the ability to pick up any hand wielded weapon, regardless of its shape, and use it effectively.

To someone unfamiliar with escrima principles, that sounds presumptuous, but consider the pattern of angles again. There’s only so many ways to hit an opponent.”

By simple definition, an improvised weapon is a found object used as a weapon.

The physical attributes of a found object (edged, blunt, pointed, flexible, projectile) will dictate how it could be used as an improvised weapon.

In using improvised weapons, the escrimador must also decide on the degree of force that he wants to use to neutralize a threat. The following narrative of an encounter fought by the late Grandmaster Angel Cabales while working in a fish packing house in Alaska, published in “The Filipino Martial Arts” perfectly illustrates this point: “Cabales backs off and walks away with their laughter following him out the door. In the bunkhouse he unsheathes his knife.

The bunkhouse superintendent, another Filipino, runs to his side. “No! No killing here! Please, no killing!” He knows about the trouble in the packing house. It’s trouble that’s been brewing for a long time and he knows it will only get worse with a knifing.

Instead of rushing out, Cabales pulls down the little Christmas tree in the bunkhouse and uses his knife to cut away the branches. When he finishes, he has a smooth, tapered stick of supple pine. He moves outside with the stick and the men are waiting. There are seven now, lined around the Filipino shack, and six have large clubs of driftwood.”

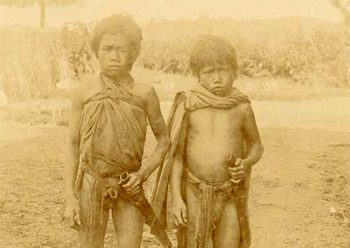

Filipinos through centuries of warfare were known masters of improvised weaponry. The Igorot of northern Luzon and the Moro pirates of Mindanao for instance were notorious for throwing rocks with deadly force and accuracy during battle. Albert Ernest Jenks in his book “The Bontoc Igorot” (1905) wrote of how the former develops this deadly skill since childhood, “The game is a combat with rocks, and is played sometimes by thirty or forty boys, sometimes by a much smaller number.

The game is a contest—usually between Bontoc and Samoki—with the broad, gravelly river bed as the battle ground. There they charge and retreat as one side gains or loses ground; the rocks fly fast and straight, and are sometimes warded off by small basket-work shields shaped like the wooden ones of war.

They sometimes play for an hour and a half at a time, and I have not yet seen them play when one side was not routed and driven home on the run amid the shouts of the victors.”

But perhaps the most amazing improvised weapon of pre-colonial Filipinos is the bagakay. The bagakay is a very simple weapon, just a piece of bamboo with points sharpened.

Anybody can make a bagakay but I doubt if the level of skill by which the ancient Filipinos wielded it can be duplicated in modern time. A Spaniard’s account on the use of the bagakay was included in “The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898 Volume XL, 1690–1691,” edited and annotated by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, it reads, “The arms used on sea and land—besides those of the plain, in places where the people fortify themselves with the resolve to defend themselves—in addition to the one mentioned (which are the most deadly), are the bagacayes, which are certain small bamboos as thick as the finger, hardened in the fire and with points sharpened.

They throw these with such skill that they never miss when the object is within range; and some men throw them five at a time.

Although it is so weak a weapon, it has such violence that it has gone through a boat and has pierced and killed the rower. Brother Diego de Santiago told me, as an eyewitness, that he being seated saw that thing (which appears a prodigy) happen in the same vessel in which he had embarked with a garrison.

To me that seemed so incredible that I wished immediately to see it myself; and, cutting a bagacay, I had it thrown at a shield. In Samboanga [Zamboanga] I saw a bull which was killed immediately by a bagacay which a lad threw at it, which struck it clear to the heart.”